Unmade words

The tyranny of the blank page

For a writer, there are few things quite so intimidating as a blank page. It stares you down like a playground bully, daring you to make the first move, while you hang back, knowing that, all too often, the first move is the wrong move. But then you take your courage in your hands and write a sentence, and the page sneers back at you, ‘That your best shot? Really?’ and you have to admit that it was rubbish, and so you have to get back up, dust yourself off, hit delete and start all over again. And that’s part of the process of writing.

There are all sorts of exercises recommended for emerging writers to help defeat the blank page bully, and very helpful many of them are. Fundamentally, though, there is only one thing to do, and that is actually write - or, as Jack London memorably put it, “Go after it with a club.” Nothing is so good for your writing as sitting down and doing it.

Of course, reading matters too, particularly reading works in which the use of language resonates with you - and those works can be found in all sorts of unexpected places, as well as in the Literary Canon that was fired towards us in our schooldays. For instance, I have just subscribed to a Substack - The Empty City: A Law and Polity Blog - for the awesome purity and clarity of its language. The views expressed are, to be sure, interesting and informative, but it was the author’s silky touch with words which, for me, tipped the balance from ‘free’ to ‘paid’.

But, when, in our own writing, the wrong word is so readily and stickily to hand, how on earth are we to find the right one? And it’s not really helpful to say, ‘You’ll know it when you see it.’ That’s true of course, but it just begs the question - how are you going to be able to discern it when it remains so resolutely out of reach?

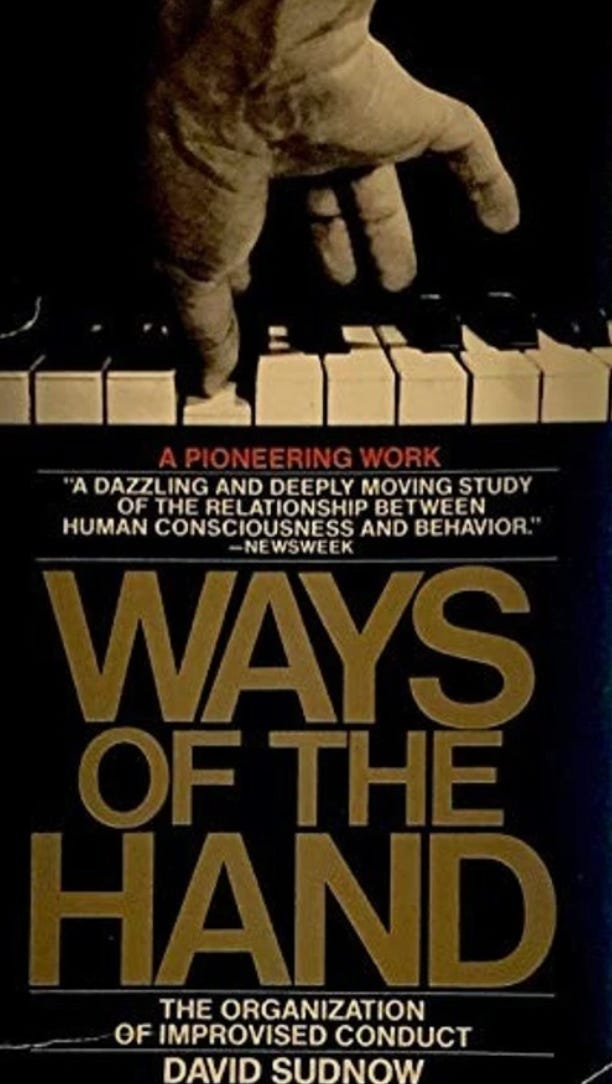

Here I am going to take what may seem like an unexpected detour, and draw briefly on an interesting passage from Jeffrey A. Bell’s Deleuze’s Hume: Philosophy, Culture and the Scottish Enlightenment. In order to explore Gilles Deleuze’s “understanding of the reality of the virtual” (something I’m not going to go into here, you’ll be relieved to know), Bell refers to a work by David Sudnow entitled Ways of the Hand. This is a fascinating book, unfortunately now out of print, but available secondhand. It is, in Bell’s words, “a book that describes in minute detail the processes and challenges Sudnow encountered in learning improvisational jazz.” For Sudnow, once he was adept at the keyboard, ‘the prime question in trying to make up melodies with the right hand, was, Where?’

“In other words,” Bell goes on, “in encountering the virtual reality of the notes, for the notes are indeed real, the problem in making up melodies is precisely in how to actualise these melodies, where to go with the virtual so that it becomes an orderly actual.”

Sudnow asked his teacher for guidance, who reluctantly gave him a list of devices - jazz-sounding scales, runs and so forth, that Sudnow then incorporated into an expanding repertoire of skills. But these were predetermined paths, this was not improvisation. This meant that “rather than encountering the multiplicity of melodic paths and actualizing it in a sustained path, Sudnow instead found himself lunging for a melodic path that was prefigured.” The change came when, in contrast, he learned to affirm the multiplicity and “let it sing in a jazzy way.” As Sudnow himself said, he realised ‘there is no melody, only melodying.’

In the same way, I would argue, for writers there is no sentence, only sentencing, even, perhaps, no word, but only wording. But what, both conceptually and practically does that mean?

In a lecture he gave in 1914, Robert Frost spoke of ‘unmade words’. He was stating here his desire not use the language “that everybody exclaims Poetry! at,” but, as with a lot of Frost’s writing, the term ‘unmade words’ resonates far beyond its apparent simplicity.

An unmade word is not like an unmade bed. For an unmade bed, you have the finished article prefigured - a tweak of a duvet corner here, and a puff of a pillow there, and it’s all done. But an unmade word exists in a world of the virtual, of words unspoken, one amongst a multiplicity, an excess of words which continue to resonate even when the unmade word is then made actual.

Just as a jazz musician ‘melodies’, so a writer ‘words’ - and in that wording, worlds are made. And that’s why it is so difficult, so intimidating, and, just occasionally, so satisfying. In the end it is not that there is a single right word - a Platonic Form of x meaning y that you can hunt down through the thickets of your mind. Rather there will be a word which, plucked at the right time in the right way, will resonate with what you are seeking to say, and what your reader, in their turn, is seeking to see, or experience, or know. And, at that moment, the word, the sentence, the text, will come to rest, and, as in Ted Hughes’ The Thought Fox, “The page is printed.”