A few months ago, I wrote an article about making meaning that scratched a little at the surface of this vast and taxing topic. As I spend my days writing stories of different kinds, it’s a subject that’s never far from my mind. So why do we like stories so much? Or, to put it even more emphatically, why we do need stories?

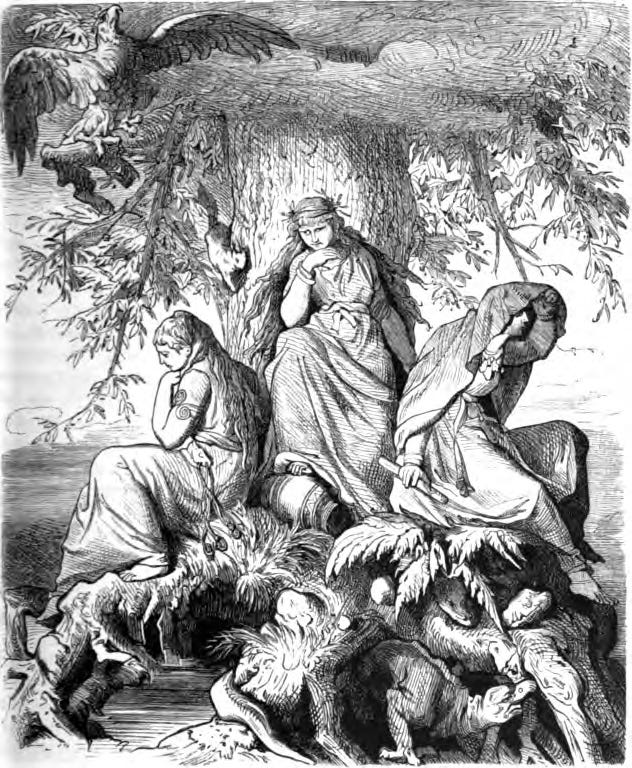

In Norse mythology, there are three cloaked women, Urðr (Past), Verðandi (Present), and Skuld (Future), who sit at the roots of Yggdrasil the World Tree, spinning the threads of human fate. They are the Norns, who hold in their hands the lives and deaths, the triumphs, humiliations, and sudden setbacks, of all humanity. And if you’ve ever had a go at spinning, or even if you’ve just once held a strand of wool in your hands, you’ll know how easy it is to tangle the thread or to snap it apart - it’s a superb metaphor for our experience of life, with its knots and twists and abrupt reversals. And perhaps that’s part of why we like stories - it’s reassuring to feel that there’s some kind of logic to our lives, even if that logic is all but indiscernible, and lies in the hands of a bunch of rather grumpy-looking women.

But, it seems, there is more to it than that - it is actually in our chemistry to respond to stories. In 2015, the American neuroscientist Paul Zak published a paper detailing how, when people are engaged in a story - particularly a story which moves us emotionally - our brains release the feel-good hormone oxytocin. Oxytocin is, according to Zak, “an astonishingly interesting molecule. It is a small peptide synthesised in the hypothalamus of mammal brains. It is made up of only nine amino acids and is fragile.” It is commonly associated with the hormones released during child-birth and breastfeeding, which makes it handy enough, but, according to Zak, it is also involved in our social interactions, and this is where it links up with story-telling.

When people like and trust us, our brains release oxytocin, which encourages us to build social bonds, simply because it makes us feel good. Imaginative engagement, or narrative transportation as psycholinguists call it, triggers the same empathetic responses as we experience in daily life, rewarding us with a pleasant dollop of oxytocin.

It does, though, have to be an engaging story. Zak’s lab studies have made it plain that a dull narrative evokes no such delightful feelings, but rather an indifferent mental shrug and a shift of attention to something that might, perhaps, be more interesting.

As a reader, though, once you’ve found a writer you know, like and trust, and whose skilfully spun narratives engage you, then you know you can be sure of a deeply pleasing oxytocin hit. And it’s legal.