I have spoken a good deal about the wriggly things that swim around and under the words we use, given them resonance and substance and flavour. But there are times when you just want to write as clearly as possible. Instructions, exam questions, information books - particularly information books for children - all require a kind of lucidity which is highly difficult to achieve. In fact, I would say that though cleanliness may be next to godliness, clarity is next to impossible. Especially in English.

I learnt this hard lesson when I was working as a professional translator and author of information books for young children, and as an editor and writer of texts and textbooks for secondary-age schoolchildren.

A quick aside - the information books for young children were particularly fun and challenging, because the publisher that I was working for would buy the illustration film (ie with all the pictures already laid out on the page) from the original, French, publisher, and I would need to write text that both matched the illustrations, and fitted into the spaces which had been left for text on each page. One series, still available today as ‘My First Discoveries’, had clear acetates interleaved with the text pages - the acetates were printed with an illustration, and any text on the following page had to lie underneath that illustration until it was revealed by turning over the acetate. You can check them out here. They are gorgeous little books, and it was an extremely good apprenticeship in being both succinct and accurate.

So just why is clarity a problem for a writer? Part of it lies in what is sometimes (mainly by psychologists, who are perhaps themselves not renowned for their clarity of expression) called the ‘cognitive load’ - the fact that you inevitably carry all sorts of different kinds of information around in your head at the same time, some of which is vital to the task in hand, and some of which is utterly irrelevant and needs to be winnowed out. In terms of writing clearly, I would say, there are four particular items which you do have to hold on to if you’re to achieve your goal:

What you need to say

Who you are speaking to

What they need to know

The outcome you want to achieve

As you’re writing, and particularly as you’re editing, each of these will come in and out of focus, until, on a good day, with a following wind, they are all in balance, and you, your words, and your reader, will all be in harmony together. A consummation devoutly to be wished, as William S so knowingly - and clearly - said.

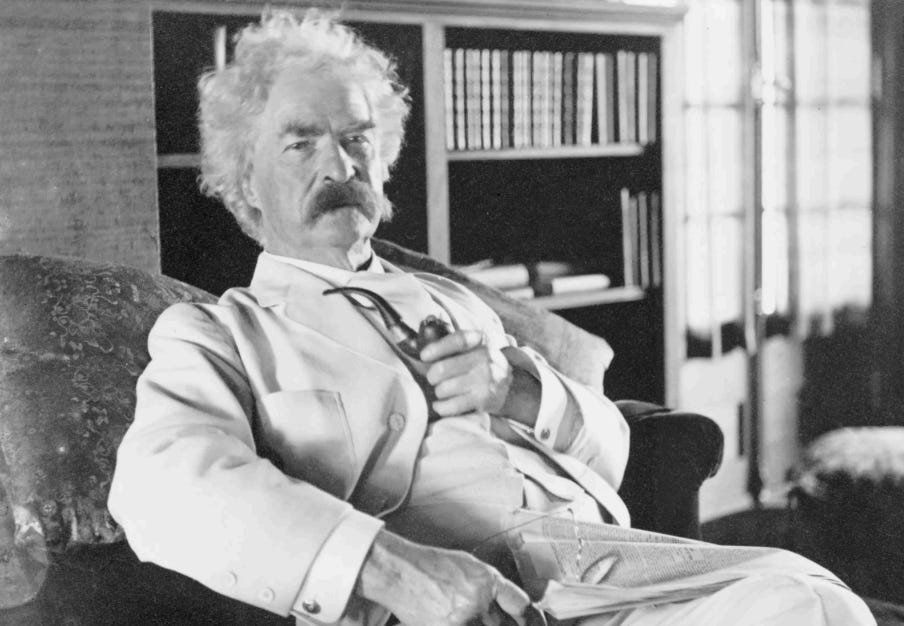

So why is this so especially difficult in English? Because the English language is a hoarder - it’s got piles of words from all over the world, Latin, French, German, Hindi, Hawaiian, all teetering together, until you can barely find your way through to the word you know you want, which is, you’re certain, definitely there somewhere… And, as Mark Twain once said, “The difference between the right word and the almost right word is the difference between lightning and a lightning bug”.

As with so many things in life, the heterogeneity of the English language is both a blessing and a curse. But for precise communication, and especially for information writing, I would almost always opt for words with Anglo-Saxon roots. Although the meaning is almost exactly the same, there is a world of difference between “Keep Clear” and “Maintain Unobstructed”.

The author Bill Wheeler has said, “Good writing is clear thinking made visible,” and clear thinking is damned hard work. So, to finish with another superb quotation from Mark Twain, “Please forgive me for writing such a long letter - I didn’t have time to write a short one.”

Great quote to end with!